Mental Health for the Young & their Families in Victoria is a collaborative partnership between mental health & other health professionals, service users & the general public.

Mailing Address

MHYFVic

PO Box 206,

Parkville, Vic 3052

PROJECT EVIDENCE for Prevention of Mental Disorders.

The project coordinator is Dr Allan Mawdsley. The version can be amended by consent. If you wish to contribute to the project, please email admin@mhyfvic.org

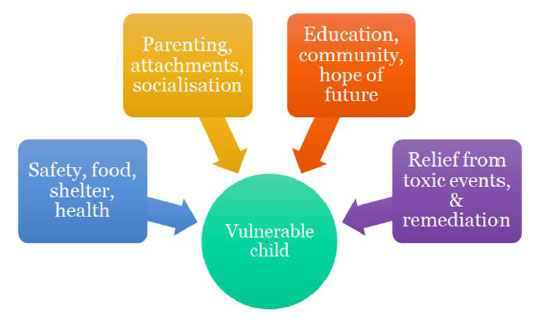

[1] Universal Programs. Universal programs are desirable because they have the potential to reduce the community prevalence of mental disorders whereas Selective and Targeted interventions only focus on small sub-populations. A discussion of this can be found in the 2018 Winston Rickards Memorial Oration. [Link] The Oration put forward the hierarchy a,b,c,d below, based on the World Health Organisation literature on Prevention of Mental Disorders.

These aspects of prevention form a kind of hierarchy of significance, somewhat similar to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. If you are in a war zone, unsafe, with no reliable food and water, no shelter and no support services, there is a high level of stress and not much else matters. Once those basic needs are met there is time to look at family functioning and parenting. Enhancement of attachment and pro-social behaviours then become feasible, paving the way for processes to reach one’s potential and to respond to individual therapeutic interventions.

[1 c] Education to potential

Better education equates to better jobs and a higher standard of living. Ipso facto, education is important. However, education is not just about jobs, it is about the development of the whole person. This includes the person’s mental health. The seminal Perry Preschool research program showed that quality pre-school education changes the whole life trajectory of the child. Not only is there an economic benefit over the life span from better jobs and less reliance on welfare support, more importantly there is benefit from greater family stability.

This means lower rates of family breakdown and lower rates of involvement in the criminal justice system. Such benefits extend to the next generation. In all, it was estimated that the benefits were about sixteen times the costs of providing that quality early education. Isn’t it amazing that our society begrudges spending more on quality education but finds more and more money to spend on putting people in prison.

The psychological benefits are at many levels. At a basic level, schooling is to children what employment is to adults. Successful employment is at the core of personal identity. It is central to self-esteem. The mental health of unemployed people is significantly at risk. So it is with children. If they are not succeeding at school, their mental health is at risk.

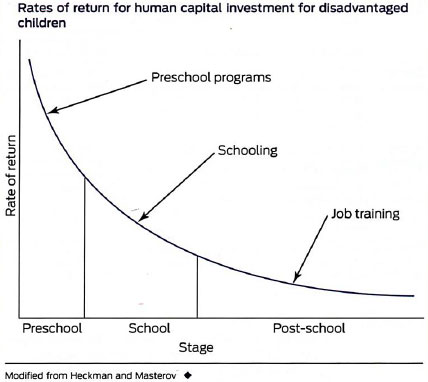

At the highest level, education enhances self-actualisation, participation in the arts and sciences, and personal well-being. The earlier we start, the greater the impact. The beneficial effects of education are greatest in the early years, as illustrated by this graph of the impact on developmental progress of input at various stages.

Early childhood education

The concept of the kindergarten as a place where children’s social, emotional, cognitive and language development could be enhanced along with their physical health and general well-being, has been widely accepted since it was first advocated by Friedrich Froebel throughout the first half of the nineteenth century.

Although Australian Governments were slow to accept their responsibilities, kindergartens have been supported from shortly after the second world war. Despite research such as the Wood Green project demonstrating that high quality early childhood services profoundly improve the whole future life trajectories of children who receive them, and produce long term benefits many times greater than the cost, Governments are still reluctant to spend money on this means of improving the human capital of the nation.

In past years advocacy for kindergartens came primarily from the public health movement. The role was seen as enhancing the total development of the child. In recent public debate, however, the emphasis has shifted towards the early education aspect, focusing on improved levels of literacy and numeracy. It is important, however, not to assume that gains in literacy and numeracy are the only, or even the most important, benchmarks of children’s developmental progress.

The past decade has seen many examples of innovative federal and state government policy in early childhood development (ECD). These include: Investing in the Early Years: A National Early Childhood Development Strategy (COAG); the Stronger Families and Communities Strategy : national agenda for early childhood; Communities for Children; the National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education and Care; and the Early Years Learning Framework.

In addition, there is a commitment to introduce universal access to preschool, a new perspective on prevention of child abuse entitled the National Framework for Protecting Australia’s Children 2009-2020, ongoing funding for The Longitudinal Study of Australian Children (LSAC) and further funding for the Australian Early Developmental Index (AEDI).

In Victoria, the Department of Education has been retitled the Department for Education and Early Childhood Development (DEECD), the Minister for Early Children retitled the Minister for Children and Early Childhood Development.

The Victorian Children’s Council provides ongoing policy advice to the Premier and Ministers regarding child and family issues, and there are numerous examples of policy and administrative arrangements signifying that the state government understands the importance of early childhood and a universal prevention agenda.

The Creswick Foundation, through its support for prominent overseas visitors to come to Australia, has made a significant contribution by supporting the efforts of the Centre for Community Child Health (CCCH) to bring science and expertise to policy and program developments.

The initial visits by Professor Jack Shonkoff and Professor Neal Halfon helped raise awareness about the importance of Early Childhood Development. In a subsequent visit Professor Clyde Hertzman noted that mental health correlated quite strongly with general child developmental factors and that the Early Development Index (EDI) could be regarded as a proxy measure of mental health, especially the social/emotional subscale.

He asked,

Naomi Eisenstadt, Director of the Sure Start Program, visited Melbourne for two weeks from 2nd August 2005 to spread the message about the importance of community-based centres for young children and families. The basis of the program is good quality three and four year old kindergarten teaching delivered locally with family social support, integrated where necessary with child care for working parents.

This ensures that children have maximum opportunity for language and cognitive stimulation in a supportive healthy environment at a critical stage in their development. It also emphasises family support in terms of improved parenting and measures to overcome poverty and unemployment.

The message was very clear.

Money spent on pre-school child development makes a profound difference to the whole life progress of individuals. So convincing is the evidence that the British government embarked upon a five year plan to build 3500 Sure Start centres in local communities throughout the UK.

Of course, correct science is not enough. Community support and political commitment is needed for the program to be implemented. Whilst it had happened in Great Britain it doesn’t mean that it will necessarily happen here. Professor Gilliam alerted Australians to the importance of strategic communication and framing the research findings in ways that enhance likelihood of acceptance.

Professor Kahn added his perspective on measuring and improving the impact of community-based services so as to further convince authorities of their importance. Thus, advocacy must put forward a coherent, believable thesis backed up by a scientifically-sound evidence base, a cost-benefit analysis that shows not only the immediate benefit but sustained long-term gains which far outweigh the costs, and a presentation ‘story’ which makes the proposition appealing to the public. This is the field of ‘knowledge translation’.

Professor Frank Oberklaid’s University of Melbourne Centre for Community Child Health based at the Royal Children’s Hospital has been following this pathway for more than a decade. Their series of visits by eminent overseas specialists has not only highlighted the abovementioned logic but, more importantly, has engaged important decision-makers and political leaders at State and Federal levels in the evolving dialogue.

This has been extremely influential in promoting the governmental initiatives mentioned in the third paragraph of this paper. As well as successfully advocating new policy initiatives, the CCCH has actively researched the processes, finding tools to measure the current (and future) developmental status of the child population, finding effective ways in the community health arena to achieve developmental gains, and greater insight about influential factors within the Australian social context.

A key member of the CCCH team has been Associate Professor Sharon Goldfeld, who has introduced the Australian Early Development Index, a valid and reliable screening instrument for the whole population appraisal of the developmental progress of pre-school children whereby appropriate enrichment interventions may be targeted to children in need.

The federal government has supported the nationwide implementation of the screening and is encouraging improvements in service provision for children in need. The ongoing research is looking at the effectiveness of interventions and at the social determinants. Professor Goldfeld described her work in presentations at the 2013 MHYFVic Annual General Meeting and at the University of Melbourne Vera Scantlebury Brown Memorial Lecture.

Her presentation began with the proposition that healthy brain development is a pre-requisite for future health and wellbeing, and that the early phases are crucial. Plasticity of the brain decreases over time and brain circuits stabilise, so it is much harder to alter later. Health economists calculate that the return on investment in human capital in the early years is greater than at any other time in the lifespan, and that the returns far outweigh the investment.

Similarly, adverse childhood life events may have a long-lasting effect. Psychosocial factors impact upon health through recurrent stress. An index of health and social problems shows a high correlation with social inequality. This is seen within countries and between countries. Disadvantaged children have higher rates of social, emotional, communication and literacy problems, which foreshadow a lifetime of continuing disadvantage.

It is possible to make a difference. High quality early childhood education and care by well-trained staff produces greater progress. To make a population difference will require more equitable use of universal health and educational services. Targeting only the poorly performing students or the lower socio-economic students will miss the majority of students in need. Intervention must be universal but with a scale and intensity proportionate to need.

The presentation closed with an account of the trial programs being implemented in the western metropolitan region. The interventions, like those of the ‘Sure Start’ program in the UK, will need to address not only the enrichment of the children’s pre-school programs but also the family functioning and social factors.

Research is needed to identify the most effective interventions and also their cost-effectiveness to determine the best practice model for universal implementation. MHYFVic supports the concepts of universal screening and public health universal service delivery and endorses the CCCH evidence-based approach to formulating the best practice model. Further steps in this MHYFVic Project aim to incorporate the best practice model as a policy for advocacy for implementation by government.

Reference:

Schweinhart, L. J., Montie, J., Xiang, Z., Barnett, W. S., Belfield, C. R., & Nores, M. (2004). Lifetime effects: The HighScope Perry Preschool Study through age 40. Ypsilanti, MI: HighScope Press.

Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven De Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J, Zubrick SR (2015) The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Department of Health, Canberra.

The following paper by Sarina Smale adds a further dimension to the discussion of early childhood education.

The Developmental and Societal Benefits of Quality Early Childhood Care and Education

By Sarina Smale

Women’s liberation and their increased participation in the paid workforce in industrialised countries has sparked increasing demand for professional child care earlier and earlier in children’s lives. This has raised many questions about the developmental impact of the quality of early childhood care and education upon young children (Hutchison, 1999), and upon the future of society.

This paper discusses the developmental impact of early childhood care and education in a human rights context, as articulated by the United Nations (UN) Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989). These rights are outlined, followed by the features and aspects of quality early childhood care and education that may promote children’s rights to healthy development.

The impact of such care and education upon children’s readiness for school is also considered in the context of these rights. An economic argument for the provision of quality early childhood care and education as a public good is next presented, followed by an argument for universal provision as a means to serve children’s rights to non-discrimination.

The medium and long term benefits of quality preschool education are then illustrated, with reference to a particular example of an American preschool program for children in poverty. These benefits are shown to have promoted the children’s life chances, but also provided a large economic return to their society as a whole. It is suggested that these benefits may accrue across more than one generation.

It is thus concluded that in promoting children’s rights through the universal provision of early childhood care and education, society as a whole may accrue large economic returns across one, and possibly two or more, generations. Further research is recommended. While this paper draws upon international literature, it does so with a special interest in the rights of Australian children and benefits to Australian society.

Children’s Rights

The UN child rights framework, with respect to early childhood, primarily incorporates the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child [(United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, 1989) and other work of the U.N. Committee upon the Rights of the Child, such as the General Comment No. 7: Implementing child rights in early childhood (2005). This framework also finds expression in the interpretative and explanatory work of the United Nations Children’s Fund [commonly known as UNICEF, (http://www.unicef.org/crc/, n.d.].

Within this framework, children are acknowledged as holding legal rights to development, play and education, exploration and learning, without discrimination (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 1989 & 2005). The Convention (1989) was ratified by 192 States, including Australia (Woodhead, 2007).

Australia’s early childhood care and education institutions could become powerful vehicles for the implementation of these rights for the children in their care. The provision of quality care and education could realize, and support the further realization of, children’s rights, including particularly their rights to development and to education.

Key features of such quality in early childhood care and education, promoting children’s development, are next discussed.

Features of Quality Child Care and Education that Promote Child Development

Specific key components of a quality caregiving environment for young children have been identified as the encouragement of exploration, mentoring in basic skills, celebration of developmental advances, guidance in rehearsing and extending new skills, a responsive and rich language environment and protection from inappropriate punishment, disapproval or teasing (Hertzman, 2004 cited by Mawdsley, 2004; National Crime Strategy Australia, 1999).

In tune with this, but at a more general level, the United States’ National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network (2000) asserted that sensitivity and responsiveness and positive affect on the part of the caregivers, and frequent verbal and social interaction and cognitive stimulation in child care are critical in promoting development. This development may be considered in terms of four domains of development, namely the cognitive, language, physical and social-emotional domains.

To create the conditions for such features, the United States’ National Research Council (1990, cited by Hutchison, 1999) has proposed as essential, maximum child-staff and group-age ratios. This Research

Council recommended no more than three infants, four toddlers or eight preschoolers to each staff member, with no more than six infants, eight toddlers or sixteen preschoolers in one group.

Domains of Child Development: Enhancing these through Early Childhood Care and Education

Child development literature sees the human life span in terms of sensitive or critical periods, when interventions may be most effective (National Crime Strategy Australia, 1999; Western, 1999). For instance, certain key elements of cognitive development peak between birth and age four, making early childhood a uniquely beneficial period for promoting cognitive development (Hertzman, 2009a & 2009b); Hertzman 2004, cited by Mawdsley, 2004).

Cognitive development

Some important aspects of cognitive development include perception and memory, constructing reality and processing experience (Western, 1999). Hence it is an important part of mental health and well being (Western, 1999). Furthermore, early childhood cognitive development provides the grounding for later literacy and numeracy.

The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network (2003) found a significant and positive relationship between the quality of child care from 6 months to 4.5 years and all measures of cognition assessed at 4.5 years of age.

Language development

Language development includes a child’s capacity to communicate his or her needs and to understand others, including clear articulation, vocabulary and grammar (Berk, 2006; National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research, 2000).

It may also be significantly facilitated in early childhood (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research, 2000). For instance, the more a child is verbally engaged by a caregiver, the greater the development of comprehension and own vocabulary (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research, 2000).

Physical development

Physical development involves growth and the development of fine and gross motor skills involved, for instance, in writing and self-care (Berk, 2006; Nilsen, 2008). Although the field of literature deals less with the physical developmental impacts of quality child care and education, there is agreement that development of motor skills seems facilitated by care environments that support physical movement and exploration of these skills (Nilsen, 2008; Hutchison, 1999).

Social- emotional development

Social- emotional development includes the development of children’s self-esteem and social skills including social problem solving, the regulation and articulation of emotions, and the capacity to empathise with others (Berk, 2006; ). It also concerns the attachment relationships children develop with their caregivers (Berk, 2006; Hutchison, 1999). Dodge (1995, cited by Hutchison, 1999, p.133) stated, in Hutchison’s words, that quality day care “can promote social competence, a positive sense of identity, [and] trust in others”.

Moreover, Berk (2006) reported that Australian children in high quality child care environments generally developed more secure attachment relationships than those in other forms of child care. Furthermore, Griffith (1996, cited by Hutchison, 1999) found that attendance in quality day care encouraged and supported the development of greater “prosociability” in children.

Citizenship, in the sense of participation in society, appears an important area of social development. Pramling Samuelson, Sheridan and Williams (2006) identified a focus upon children’s development as democratic citizens as a feature of quality in early childhood care and education. Beyond cooperation, this may involve children learning how to respond to the needs of others, and to differences between people, in respectful ways (McNaughton, 2006).

Children, as social actors, may be encouraged to engage in, and learn from, participation in everyday decision making (Woodhead, 2006). They may also be supported in developing skills in advocacy for equality and justice (MacNaughton). Although there appears less formal research regarding the success of early childhood programs in promoting this area of social development, anecdotal evidence certainly suggests such success.

School Readiness: Impact of Experience Prior to School

School readiness may be defined as a child’s accessible potential, or readiness, to engage appropriately in school life, and to derive benefit from school activities.

Like many others, Hertzman (2009c) has stated that a child’s capacities to perform at school is significantly influenced by aspects of development, particularly social, cognitive and language development, prior to school. As observed above physical development plays a significant role in the capacity to write and for self-care by school age too (Berk, 2006; Nilsen, 2008).

Much literature has argued that school readiness may be enhanced by the promotion of earlier development through quality child care and education. While the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research (2000) reported mixed research findings, they cited Field’s (1991) and Rosenthal’s (1994) findings that quality of infant care is associated with later academic and cognitive performance in primary school.

They also cited a Swedish study, by Broberg, Wessels, Lamb, and Hwang (1997), which found that higher quality of care in the first three months of life predicted mathematics performance at age seven.

Broberg and colleagues (cited by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research, 2000) also showed a sleeper effect for literacy development, in that greater verbal skills at age seven were associated with high quality centre-based child care before age three, even though these beneficial outcomes were not actually evident at age three (Broberg et.al., 1997, cited by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research, 2000).

In terms of other benefits to children of successful engagement in school, the National Crime Strategy Australia (1999) suggested that increased self-esteem may also follow when a child performs well at school.

The academic success and self-esteem of school-aged children may be seen to powerfully represent the successful promotion of their rights to development and education, amongst others. A country’s ability to promote these rights for school aged children appears to depend upon its previous success in promoting these same rights for the children when younger. Promoting these rights may generate advantages beyond those accruing to the holders of these rights (the children themselves).

The Promotion of Children’s Rights, through Early Childhood Care and Education, as an Economic Public Good

The OECD (Organisation of Economic and Cultural Development, 2006) cited Alakeson (2004) in pointing out that money invested in children’s early care and education can be more productive than money spent upon remedial education for “young school drop outs and adults with poor basic skills” (p.38). The OECD (2006) also cited the work of Nobel Prize winning economist, Heckman, and colleague, Cuhana (2005), in graphing the negative association between the age of an individual and the rate of return upon investment in their education.

This is compatible with Hertzman’s findings that early intervention may have greater benefical impact due to the early sensitive period of significant aspects of cognitive development (Hertzman, 2009a &20009b; Hertzman, 2004, cited by Mawdsley, 2004).

Cleveland and Krashinsky (2003) were cited by the OECD (2006) in referring to early childhood education as a public good. More accurately, it may be described as a public service, defined by economicst Mansfield (1994) as a services from which all may benefit without an additional cost attached to the benefit obtained by an additional person, and from which no person can be excluded from enjoying the benefits.

According to the OECD, the public benefits to be enjoyed from investment in early childhood care and education include its contribution to “the general health of a nation’s children, future educational achievement, labour market volume and flexibility and to social cohesion” (p.37).

The OECD (2006) argued that “early childhood services deliver [positive] externalities” (p.36). A positive externality may occur when the social benefit arising from the production of a good remains uncompensated through the price mechanism (Cullis & Jones, 1992). In this case, it appears that the public, or social, benefits derived by society from the care and education provided by early childhood services, is greater than the market price paid for them.

Cullis and Jones (1992) indicated that where positive externalities occur, too little of the relevant goods are produced, which is not optimal, or efficient, in economic terms. In today’s society, early childhood institutions are not paid sufficient money to provide the amount of quality care and education that would be most beneficial to society as a whole.

Children’s Rights to Non Discrimination

Another rights-based argument for the provision of quality early childhood care and education concerns poverty and discrimination, with respect to children’s right to nondiscrimination, an Article of the United Nations (UN) Convention (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2006b; OECD, 2006).

A nation’s capacity to promote children’s right to survival, health and development appears to depend upon its ability to realise their rights to such things as adequate health services and opportunities to be played with, perhaps sung to, by their caregivers (UN Committee on the Rights of the Child, 2005).

Such opportunities, to which children have rights according to the United Nations Convention, were referred to by Gilley and Taylor (1995) as contributing to the “life chances” of children (p.1). According to Gilley and Taylor, access to and quality of education positively influences the life chances of pre-school aged children. Hence, the provision of quality early childhood care and education to all children, without discrimination, would seem to promote the right of all those children to survival, health and development, as well their right to education, per se.

While Gilley and Taylor (1995) discussed the negative impact of poverty upon childrens’ life chances, they raised other factors negatively influencing the life chances of children not living in poverty as well. Universal provision of early childhood services may mediate the impact of such negative influences upon the life chances of all children. Hertzman (2004, cited by Mawdsley, 2004) argued the desirability of such whole of population early childhood programs. The OECD (2006) also favoured the universal provision of services, without discrimination related to socio-economic status.

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989) asserted children’s right to have their rights realised without discrimination. While the life chances of children living in poverty may be increased by the promotion of their rights, children at all socio-economic levels may benefit from the realisation of their rights and the amelioration of factors negatively impacting upon their life chances.

However, research in this field, to date, has focussed upon demonstrating the developmental benefits of quality child care and education primarily in the context of socioeconomic disadvantage (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research, 2000; OECD, 2006). Hence the broader public, or social, benefit of satisfying children’s rights to survival, health and development, as well as education and non-discrimination, has been primarily highlighted with respect to children in poverty.

The discussion below is offered as a demonstration of the benefits to society of satisfying children’s rights to survival, health and development, to education and non-discrimination through the provision of quality early childhood care and education. It is not intended as an argument for discrimination against satisfying the rights of children across the socioeconomic spectrum, through universal service provision to them.

Nor does it suggest that the public and societal benefits of service provision, to children whose life chances are limited by factors other than poverty, may not be substantial.

Impacts of Quality Preschool Education and Children of Low Socio-Economic Backgrounds:

The Evidence of the Perry Preschool Program

One example of a preschool program evaluated to be successful is the Perry Preschool program. The Perry Preschool program was an American preschool education program for young children living in poverty in the state of Michigan (Schweinhart 2005; Parks, 2000). It commenced in 1962 (Highscope, 2007).

The evaluation of the program has focussed upon medium and longer term impacts of the program, not only upon the children’s life chances, but also upon broader society. Furthermore, when these impacts are considered in the light of National Crime Strategy Australia’s (1999) research, they can be seen to imply transgenerational benefits for the children’s future families and society as a whole.

Medium term benefits of quality preschool education

On the basis of a controlled study, the evaluation showed that the benefits of quality preschool may extend beyond school readiness and performance in primary school, to success at high school. Sixty- five percent of the children who attended the early childhood program graduated high school, in contrast to the majority (55%) of the control group who did not graduate high school (Schweinhart, 2005). They held better attitudes to school and education and outperformed the control group in literacy and other tests of academic achievement (Schweinhart, 2005).

Furthermore, more of the children who attended the preschool program grew into adults aged 40 years old experiencing the following benefits, according to (Schweinhart, 2005).

These adults reported higher levels of employment, higher incomes, and higher levels of home and car ownership than those within the control group. They reported using less medication, such as sedatives and tranquilisers, or illegal drugs such as marijuana and heroine. They reported more convivial family relationships and more of the men indicated they were raising their own children than those in the control group. They also reported utilising social services such as family counselling services and General Assistance less than the control group.

Longer term benefits of quality preschool education

The longer term benefits identified as flowing from the Perry Preschool program included, first, the economic return to society in relation to the children who attended the Preschool. The total economic return of the Perry Preschool program was estimated to be US $17.07 per US$1 invested, in constant 2000 US dollars (Schweinhart, 2005).

It was conservatively estimated based upon reduced government expenditure and increased taxation income (Schweinhart, 2005). This included welfare and education savings, crime savings and increased taxation due to higher earnings (Schweinhart, 2005). Approximately 75% of the return per dollar went to society at large, primarily (88%) through reduced crime.

The savings through crime prevention may be better understood in the light if the work of the National Crime Strategy Australia (1999). The other short and medium term benefits to participants in the preschool program appear to serve as protective factors and/ or reducing risk factors for criminal activity.

Crime savings: Prevention

The National Crime Strategy Australia (1999) considered risk and protective factors for crime within the children’s development. These risk factors included those related to developmental difficulties such as poor problem solving, low self esteem, school failure and peer relationship issues (including bullying, peer rejection and membership of deviant peer group) (National Crime Strategy Australia, 1999).

Protective factors, related to development, include social competence, social skills, problem solving and school achievement, membership of a prosocial peer group, having a sense of belonging or bonding and having opportunities for success at school (National Crime Strategy Australia, 1999).

Realising children’s right to development and their school readiness, contributing to the realisation of their right to education, would appear to promote the development of protective factors and potentially reduce risk factors for crime. Furthermore, the National Crime Strategy Australia (1999) identified other ways in which quality preschool education may increase protective factors.

The National Crime Strategy Australia (1999) stated that preschool programs providing cognitive enrichment, encouragement of child- initiated learning and responsibility, family involvement and a combination of child training and parenting programs have several desirable outcomes.

These include better school performance, fewer child behavioural problems, improved parenting skills, greater income and reduced rates of serious offending. Hence, the promotion of protective factors for criminality, and the reduction of risk factors, would appear to represent the promotion of the life chances of children across the economic spectrum.

Transgenerational benefits of quality preschool education, including crime prevention

The beneficial impact of the Perry Preschool program upon the adult lives of its participants, as outlined by Schweinhart (2005), seems to provide transgenerational benefits. It would appear that the Perry Preschool program may have indirectly but significantly increased the life chances of, and reduced risk factors for substance use and criminality in the lives of, the children of its participants as the next generation.

The National Crime Strategy Australia (1999) identified the absence of the father, long-term parental unemployment, negative family interaction, divorce and family break-up, socioeconomic disadvantage and housing issues as risk factors. Factors such as father absence, negative family interactions, divorce and family break-up in particular would not appear limited to the lives of children living in poverty.

However, the occurrence of these factors were all reduced within the families formed by those adults who had attended the Preschool program as children, compared to the family lives of the control group.

Perry Preschool Program, example only of quality in early childhood care and education

It is important to note that Woodhead (2006) argued that early childhood care and education programs are specific to their local contexts and it is not here suggested that the Perry Preschool Program ought to be applied wholesale to wider social contexts. It is discussed here as one many examples of successful early childhood care and education programs. Woodhead (2006, p.18) acknowledged “the overwhelming weight of evidence” supports the success of quality early childhood programs around the world.

Conclusion

Research to date strongly supports the view that universal provision of high quality early childhood care and education promotes the rights of children to survival, health and development, to education and to non-discrimination. It promotes their cognitive, language, physical and social- emotional development, as well as their chances of academic success and self esteem at school, significant factors in school readiness.

More broadly, it appears to increase or enhance their life chances. Benefits extend to others beyond the holders of these rights, the children, especially in terms of economic returns to all members of society, for at least one, and possibly two or more generations. These returns with respect to service provision to children in poverty, have been shown, through examples such as that of the Perry Preschool Project, to potentially be at least 17-fold in the first generation, occurring primarily through crime prevention.

Crime prevention is obviously socially beneficial at many levels and is important at many levels across the socio-economic spectrum.

However, it is also important to recognise all children, again across the socio-economic spectrum, as potential contributors of creativity and productivity to society, to the economy, and to the lives of the next generation after them. Such positive outcomes may be actively promoted in the present by, first and foremost, seeing children as the holders of human rights and promoting these rights, including their life chances and opportunities to develop the skills and attributes necessary to make these contributions.

Further research concerning the economic returns of quality universal early childhood care and education programs, in Australia, appears to be warranted. Further research may also be valuable into the sort of public policy and regulatory framework that may better promote the human rights of children through quality early childhood care and education.

REFERENCES

Berk, L. E. (2006) Child Development, Boston: Pearson, Allyn and Bacon.

Cullis, J. & Jones, P. (1992). Public Finance and Public Choice, London: McGraw- Hill Book Company.

Hertzman, C. (2009a) Population health and the Early Years- Mustard Lecture. Accessed July 13, on websitehttp:www.earlvlearning.ubc.ca/presentations general.htm

Hertzman, C. (2009b) Seven uses of the EDI: The Case of BC. Accessed July 13, on website: http:www.earlylearning.ubc.ca/presentations general.htm

Hertzman, C. (2009c) Child Health Presentation. Accessed July 13, on websitehttp:www.earlylearning.ubc.ca/presentations general.htm

Hertzman, C. (2004) ECD Research: Partnerships to Help Make Better Decisions: The Early Child Development National Crime Strategy Australia ing Project, Accessed Sept 7, on website:http://www¦earlvlearning¦ubc¦ca/documents/Hertzman%20sept%207%202004¦pdf

Highscope (2007) Perry Preschool Study. Accessed Oct , 1on website: http://www.highscope.org/Content.asp?/ContentId = 219

Hutchison, E.D. (1999) Dimensions of Human Behaviour: The Changing Life Course, Thousand Oaks, CAL: Pine Forge Press

MacNaughton, G.M. (2006). Respect for diversity: An international overview. Accessed 2008, on

website:http://www.bernardvanleer.org/publication store/publication store publications/re

spect for diversity an international overview/file

Mansfield, E. (1994) Microeconomics, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Mawdsley, A. (2004) Report on Clyde Hertzman Workshop, RCH 20/10/2004, Unpublished

Paper, Melbourne: Creswick Foundation.

National Anti-Crime Strategy Australia. National Crime Prevention (1999) Pathways to Prevention: Developmental and Early Intervention ANational Crime Strategy Australia roaches to Crime in Australia, Barton, ACT: National Crime Prevention, Attorney- General’s Department

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network (2003) “Does Quality of Child Care Affect Child Outcomes at Age 41/2?” in Developmental Psychology, Vol. 39(3), May.

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Early Child Care Research Network (2000) “The Relation of Child Care to Cognitive and Language Development” in Child Development, Vol. 71, No. 4, July/ August.

Nilsen, B.A. (2008). Week by Week: Plans for Documenting Children’s Development, Thomson, Delmar Learning.

OECD (2006). “Starting Strong II: Early Childhood Education and Care”, Source OECD Social Issues, Migration, Health, vol.2006, no.1, pp.1-445.

Parks, G. (2000). The High/ Scope Perry Preschool project. Juvenile Justice Bulletin, U.S. Department of Justice. Accessed Oct 10, 2007, on website: h tt p/www.ncirs.gov/pdffiles1/oiidp/181725.pdf

Samuelson, Sheridan & Williams. (2006). Five Pre-School Curricula-Comparative Perspective. International Journal of Early Childhood Education, 38(1),11-26.

Schweinhart, L. J. (2005). The High/ScopePerry Preschool Study Through Age 40:

Summary, Conclusions, and Frequently Asked Questions. Accessed Oct 10, 2007 on website: http://www.highscope/Research/PerrvProiect/PerrvAge40Su mWeb.pdf

United Nation’s Committee on the Rights of the Child (2005). General Comment No.7: Implementing the Rights of the Child (2005), Forty-First Session, Geneva, 9-27 Jan.

United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child (2006b) A Guide to General Comment 7: ‘Implementing Child Rights in Early Childhood’. The Hague : Bernard van Leer Foundation

Western, D. (1999), Psychology: Mind, Brain and Culture, NY: John Wiley and Sons

Woodhead, M. (2006) “Education for All Global Monitoring Report 2007 Early Childhood Care and Education ‘Changing perspectives on early childhood: theory, research and policy'” International Journal of Equity and Innovation in Early Childhood, vol.4, no.2, pp. 5-8

Primary schooling

Whilst family and early life experiences provide a foundation for further progress, the years of primary and secondary schooling are crucial in setting the whole life trajectory of a young person. Just as employment is central to an adult’s sense of achievement and self-worth, successful participation in schooling is central for the child. Successful participation is not merely progress in literacy and numeracy but in the total development of the young person in all of the domains of physical, cognitive, language and social/emotional development.

Delay in any of the developmental domains will impact upon progress as a whole. All schools should have policies which enhance the total development of their young charges. In order for schools to efficiently achieve enhancement it is necessary to have explicit goals, measures and programs in each of the domains.

There are well-accepted goals for progress in these developmental domains and programs for assessment. (See Appendix One).

This project paper seeks to describe best practice models in the social/emotional/behavioural domain, for implementation in all schools. It is acknowledged that problems in the physical, cognitive and language domains will seriously impact upon the social/emotional/behavioural domain and would need to be addressed in a wholistic approach but the focus of this project is specifically limited to the social/emotional/behavioural domain.

Project aims:

Progress to date:

There have been numerous surveys of the prevalence of social/emotional/behavioural disturbances in the childhood population, including school attenders. (See “The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents” pdf in the Library Resources section of this website). The prevalence rate varies depending upon the measurement scales used, and with socioeconomic and situational factors.

Some disorders such as anxiety and depression, the so-called ‘internalising disorders’, may impact significantly on the child’s functioning without necessarily being obvious in the classroom, whereas other disorders such as disruptive behaviour disorders, the so-called ‘externalising disorders’, may be extremely troublesome in the classroom.

However, if our aim is to gain best outcomes for our children all the problems need to be addressed, not merely the ones that are troublesome in the classroom.

When surveys are undertaken, the scope of the challenge is revealed. Allocation of resources to deal with problems thereby becomes more planful. In a sea of demands upon limited resources, what will give best value for money?

There are programs for assisting at the whole class level (universal interventions), for students who are at risk because of acknowledged vulnerabilities (selective interventions), and for the individual students who are delayed in their progress (targeted interventions). There are processes for obtaining specialist consultation and advice regarding implementation of appropriate programs.

These ideas are not new. The file “Lyndale Project” describes a secondary school intervention several decades ago. What is new, however, is the availability of simpler measurement instruments and a range of prepared intervention methods. This downloadable file can be accessed on the “Library Resources” page of MHYFVic website.

The conclusion is that all schools should undertake surveys of their student needs and implement appropriate programs with collaborative consultative support from their regional School Support Services and Regional Child & Adolescent Mental Health Services.

APPENDIX ONE

GOALS

Physical domain

Cognitive domain

Language domain

Social/Emotional domain

MEASURES

Physical domain

Cognitive domain

Language domain

Social/Emotional domain

PROGRAMS

Physical domain

Cognitive domain

Language domain

Social/Emotional domain

Reference

Lawrence D, Johnson S, Hafekost J, Boterhoven De Haan K, Sawyer M, Ainley J, Zubrick SR (2015) The Mental Health of Children and Adolescents. Report on the second Australian Child and Adolescent Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Department of Health, Canberra.

Secondary schooling

The Lyndale Project highlighted some of these issues when the High School experienced the most troublesome year nine student group that the staff had ever encountered. As an alternative to accepting an avalanche of individual referrals, the School Support Service and the staff of the school undertook a collaborative project of investigation and program development.

They undertook literacy and numeracy assessments, sociograms of friendship groupings, and individual interviews of students and staff to understand the needs. These were followed by workshops to arrive at solutions.

The findings were:

The solutions implemented were:

The following year saw a dramatic improvement in the previously reported problems. However, the task then became ‘how to maintain the enthusiasm of the teachers for the additional roles’ now that the crisis had passed. Positive reinforcement for good work applies just as much to teachers as it does to students. Full details can be downloaded.

These days, NAPLAN tests inform teachers of the literacy and numeracy challenges and ‘Mind Matters’, sponsored by the Commonwealth Government Department of Health, with resource materials available for any school that wishes to implement any of the components, provides many of the helpful approaches to problems that underpinned those at Lyndale so many years ago.

The eight Target Areas indicate the scope of the programs.

Reference

“Lyndale Project”. Mhyfvic.org Library Resources paper.

Last updated 2/2/2022

POLICES for Prevention of Mental Disorders

[1] Universal Programs

a) Safety, housing, food, welfare

b) Family functioning, parenting and Pro-social functioning (Human Capital)

c) Education to potential

d) Reduction of toxic factors

i Biological factors

ii Psychological and social factors

[1 c ] Education to potential

MHYFVic advocates that the state government, in collaboration with local government, should provide a high-quality child-care service incorporating age-appropriate kindergarten programs seamlessly progressing to primary school entry. Such an extended hours service should be available to any families that choose it, at affordable rates.

MHYFVic advocates that all primary and secondary schools should implement:

Last updated 25/12/2018

BEST PRACTICE MODELS for Prevention of Mental Disorders

[1] Universal Programs

a) Safety, housing, food, welfare

b) Family functioning, parenting and Pro-social functioning (Human Capital)

c) Education to potential

d) Reduction of toxic factors

i Biological factors

ii Psychological and social factors

[1 c ] Education to potential

It is clear that the greatest progress in child development occurs in the pre-school years in all domains – cognitive, language, physical and social/emotional. In most families the major part of children’s developmental support and enrichment comes from within family interactions supplemented by experiences outside the family. As the child grows older, more and more of the developmental educational experiences occur in society, in kindergarten, primary and secondary schooling and beyond.

Best practice requires that at every stage there will be services in partnership with families to support optimal developmental progress. This means a seamless sequence of developmentally appropriate programs, readily accessible, affordable and user-friendly, which are able to assess needs and respond individually as well as universally.

Although historically in Victoria the kindergarten movement was seen as a holistic child development program within the health domain, in recent years it has been hosted within the state Department of Education and Training domain where the holistic approach has been maintained. The facilities are predominantly provided by local government supplemented by private and non-government agencies.

The Department of Education and Training is also responsible for regulating and monitoring the network of child care facilities provided by private entrepreneurs, municipal and non-government agencies.

The historical evolution of schooling has been from a few private schools for the rich becoming supplemented by free, secular, government-run primary schools gradually enhanced to a state-wide network of primary and secondary schools covering an extended age range up to University entrance level. This system offers a choice of private schooling for those who prefer and can afford it but an option of high quality free, secular education for all children regardless of means.

The inclusion of part-time kindergarten programs has extended the schooling age range downward by one pre-school year. However, this limited additional service is insufficient for working parents whose working hours are not able to meet the drop-off and pick-up requirements of current kindergartens.

Best practice, for all who wish to use it, requires a high-quality child-care service incorporating age-appropriate kindergarten programs seamlessly progressing to primary school entry. Such an extended hours service should be available to any families that choose it, at affordable rates, provided by the state education system in collaboration with local municipalities.

Last updated 3/1/2019

We welcome discussion about any of the topics in our Roadmap epecially any wish to develop the information or policies.

Please send your comments by email to admin@mhyfvic.org

Speak about issues that concern you such as gaps in services, things that shouldn’t have happened, or things that ought to happen but haven’t; to make a better quality of service…….

Help achieve better access to services & better co-ordination between services together we can…….

Mental Health for the Young & their Families in Victoria is a collaborative partnership between mental health & other health professionals, service users & the general public.

MHYFVic

PO Box 206,

Parkville, Vic 3052

Please fill in the details below and agree to the conditions to apply for MHYFVic membership.