Mental Health for the Young & their Families in Victoria is a collaborative partnership between mental health & other health professionals, service users & the general public.

Mailing Address

MHYFVic

PO Box 206,

Parkville, Vic 3052

PROJECT EVIDENCE for Treatment of Mental Disorders. The project coordinator is Dr Allan Mawdsley. The version can be amended by consent. If you wish to contribute to the project, please email admin@mhyfvic.org

[6] Standard Treatment

a) Outpatient psychotherapies, medication and procedures

b) Inpatient psychotherapies, medication and procedures

c) Ancillary support services

[6 a ] Outpatient psychotherapies, medication and procedures

Specialist mental health services should offer a range of therapeutic programs for disabling mental health problems in the community. Service provision, clinical research and training are closely linked in the Tier Three facilities but the practice guidelines published by those services should be implemented at all levels of their service delivery facilities.

These are grouped under nine headings: (i) organic brain disorders, (ii) substance abuse disorders, (iii) psychotic disorders, (iv) mood disorders, (v) anxiety disorders, including stress-related, somatoform and obsessive-compulsive disorders, (vi) physiological disorders, including eating, sleeping and sexual, (vii) personality disorders, (viii) intellectual disability and developmental disorders including autism spectrum disorders, (ix) behavioural and relationship disorders of childhood.

All disorders in childhood require wholistic management involving caregivers. See PE4 for a general outline of case identification and assessment and PE2a(i) for infant mental health. See PE6a(ix) for a general outline of case management for young people.

PE6a (vii) Personality Disorders

Personality is the enduring pattern of social, emotional and behavioural traits that uniquely characterise each person. Personality disorders are enduring patterns which are maladaptive by deviating from cultural norms and causing distress and social disability. For communicative purposes these trait patterns are customarily clustered into a small number of recognisable types [Paranoid, Schizoid, Schizotypal, Antisocial, Borderline, Histrionic, Narcissistic, Avoidant].

In acknowledgment of the huge changes taking place during a young person’s development, it has been customary to avoid stigmatising young people with diagnoses of personality disorder until beyond age 18. Nevertheless, many of the traits are firmly established before the age of 18. Early recognition of maladaptive traits and early treatment may be of major importance to the eventual outcome, irrespective of the formal use of the diagnostic category.

Already during childhood, young people vary in their typical positive and negative emotions; capacities for self-control and positive relationships with others; feelings of empathy and warmth versus hostility and alienation; and views of themselves, others, and their life experiences.

For some youth, their typical personality patterns may begin to cause them difficulties in life; for example, their problematic personality patterns may lead them to experience high levels of distress or serious impairment in their daily lives, particularly in their relationships or self-development.

These difficulties may become severe enough for some youth to be diagnosed with a personality disorder (PD); for others, the problems may not reach clinical significance, yet may still bear negative consequences. Although there is far less research on PDs in childhood and adolescence than on other early-emerging disorders, the research that does exist has made it clear that personality pathology does occur in childhood and adolescence and poses significant risks for mental health problems and impairment both concurrently and later in life.

The study of normal development is critical for understanding pathological development. The same basic biological, psychological, and contextual processes underlie both normal and abnormal development, and therefore findings and theories from the study of normal development are relevant for explaining the development of psychological disorders.

The converse is true as well (i.e., the study of pathological development has the potential to inform research on normal development). Developmental psychology explains the development of abnormal personality through inappropriate attachment patterns and abnormal transitions between developmental phases. The main focus of research is on the following personality development related areas: the process of human development, the role of temperament and traits as personality characteristics and the role of genetic factors.

On the other hand, theoretical constructs which explain mechanisms leading to the development of personality disorders can shed more light on the phenomenon of personality disorders. Firstly, theoretical constructs include risk factor variables. Secondly, they define consistent exploratory models of intrapsychic conditions conducive to personality disorders.

Defining risk factors (including biological, environmental, temperamental and trait-based factors) within theoretical models could clarify circumstances leading to personality disorders and identify variables which build “resilience” despite the presence of risk factors. An important benefit of such a “broader” approach could be the development of prevention strategies in the case risk factors which:

Therapeutic models developed for adult patients with personality disorders, which take childhood experiences into account could be of great help for the understanding of mechanisms of abnormal personality development in childhood and adolescence.

References

Shiner, R. L., & Tackett, J. L. (2014). Personality disorders in children and adolescents. In E. J. Mash & R. A. Barkley (Eds.), Child psychopathology (pp. 848–896). The Guilford Press.

Lenkiewicz, K., Srebnicki, T., & Brynska, A. Mechanisms shaping the development of personality and personality disorders in children and adolescents. Psychiatr. Pol. 2016; 50(3): 621–629 PL ISSN 0033-2674 ISSN 2391-5854. www.psychiatriapolska.pl DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.12740/PP/36180.

Two particular examples of patterns commonly seen in young people are Antisocial Personality Disorder and Borderline Personality Disorder.

ANTISOCIAL PERSONALITY DISORDER

‘Externalising’ childhood behavioural disorders are classified in a gradation from ’Disruptive Behaviour Disorder’ to ‘Oppositional-Defiant Disorder’ and ‘Conduct Disorder’ before merging into the adult diagnostic category of ‘Antisocial Personality Disorder’. However, one half of conduct-problem children do not grow up to have antisocial personalities.

This highlights the reason why it is generally unwise to use the term ‘Personality Disorder’ for young people. Longitudinal studies aiming to document the continuity of antisocial behaviour from childhood to adolescence to adulthood have repeatedly revealed the existence of an exceptional group of children who lack such continuity.

These studies report that such childhood-limited antisocial boys develop into adult men who are depressed, anxious, socially isolated, and have low-paid jobs. Thus, boys whose conduct problems are severe and persistent enough to warrant a clinical diagnosis may not later develop antisocial personality, but they will suffer other forms of maladjustment as adults. Thus, all conduct-disorder children warrant clinical attention. The half that are destined to become confirmed personality disorders warrant early recognition and intervention.

The diagnosis of conduct disorder usually, but not exclusively, applies to older children and teenagers. They can be grouped into four classes:

The same criteria apply to the older adolescents and young adults. A difference in emphasis is the severity and pervasiveness of the symptoms of those with personality disorder, whereby all the individual’s relationships are affected by the behaviour pattern, and the individual’s beliefs about his antisocial behaviour are characterised by callousness and lack of remorse.

Coexistent with conduct disorder there may be the personality trait of psychopathy. The characteristics of the psychopath include grandiosity, callousness, deceitfulness, shallow affect and lack of remorse.

Reference

Scott S. Conduct disorders. In Rey JM (ed), IACAPAP e-Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Geneva: International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions 2012

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER

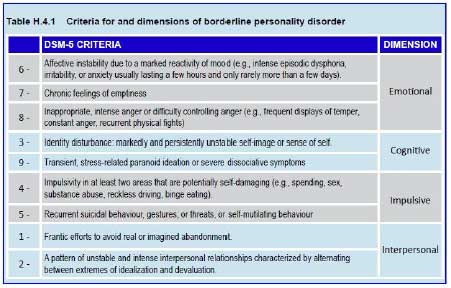

The main characteristics of BPD are instability and impulsivity, as described in the Table. The presence of five or more of the symptoms listed in Table H.4.1 is required. Also, the pattern of behaviour must be enduring, inflexible, pervasive across a broad range of personal and social situations and must cause significant impairment or distress.

These individuals’ functioning is significantly impaired (e.g., Global Assessment of Functioning scale scores around 50), with frequent job losses, unstable relationships, and history of rape. Functioning is more impaired than in other personality disorders and depression.

The risk of death by suicide in BPD patients is estimated at between 4% and 10%, one of the highest of any psychiatric illness. Suicide risk is higher in the event of co-occurrence with a mood disorder or substance abuse and with increasing number of suicide attempts. Suicide seems to occur late in the course of the disorder, around 30-37 years of age, and rarely during treatment.

Apart from physical complications ensuing from self-harming behaviours, BPD patients are exposed to risks due to their impulsivity, resulting mostly in accidents, substance misuse, and sexually transmitted diseases. Finally, instability in emotional and inter-personal relationships leads to communication problems between parents and children.

Observational studies of mothers with BPD concerning attitudes towards their infants and young children show less availability, poorer organisation of behaviours and mood, and lower expectations of positive interactions. These mothers are described more often as overprotective/intrusive and less as demonstrative/sensitive. Their children experience higher rates of parental separation and loss of employment compared to those whose mothers suffer from depression or from other personality disorders.

The cause of BPD is unknown. However, several explanatory hypotheses can be found in the medical literature. The most widely accepted theories are psychogenic. Initial explanations were based on the object-relations theory of Otto Kernberg, John Bowlby’s attachment theory and Linehan’s emphasis on the importance of emotional dysregulation.

Cognitive theories highlight dysfunctional thinking patterns learnt in childhood, which are maintained in adulthood. All these theories stress the importance of individuals’ emotional development, scarred by trauma and emotional deficits, subsequent to a failure to adapt the environment to a child’s needs.

At an epidemiological level, research has shown a significant prevalence of childhood trauma, sexual abuse, prolonged separations and neglect among patients with BPD. Although childhood trauma is high in this population, it is not present in all cases and does not always cause BPD. Nevertheless, the high occurrence of early trauma has been used to support an alternative model – as a traumatic disorder resulting from chronic childhood trauma.

Without completely explaining the disorder, repeated childhood trauma seems to be a frequent element in BPD populations and among patients with PTSD. It should be highlighted also that about half the patients with BPD also meet the criteria for PTSD.

Early maternal separation is associated with both BPD and persistence of BPD symptoms over time. Finally, BPD also has a genetic component; heritability has been estimated at 47 %. As in almost all psychiatric disorders, inheritance in BPD is polygenic. Interaction between genes and environment makes it difficult to interpret these data.

The psychological development of children with BPD mothers is affected and they tend to withdraw from their surroundings. These children are less attentive, less interested or eager to interact with their mothers, and demonstrate a more disorganised attachment in the Strange Situation Test. Children of mothers with BPD show high rates of suicidal thoughts (25%); the risk of children suffering from depression is seven times higher if the mother has a double diagnosis of depression and BPD.

Treatment

A sequential and eclectic approach offers a pragmatic solution to the clinical diversity and the natural evolution of the disorder. Determining the care framework thereby involves different aspects:

A variety of psychotherapy approaches have been used for BPD including individual, group, and crisis treatments. There is no evidence to suggest that one specific form of psychotherapy is more effective than another.

Mentalization-Based Treatment (MBT)

MBT is a psychodynamic psychotherapeutic program based on attachment theory. It assumes that disorganized attachment promotes a failure in the capacity of mentalization. MBT was first designed for BPD patients. It is currently used for broader indications such as other personality disorders or depression.

The treatment consists of group therapy combined with individual therapy, both on a weekly basis, usually in the framework of a day hospital. It aims to enhance the patient’s capacity to represent their own and others’ feelings accurately in emotionally challenging situations. The main aims of MBT are to improve affect regulation and behavioural control. It allows patients to achieve their life goals and develop more intimate and gratifying relationships.

In practice, inpatient treatment can be considered for cases with severe comorbidity (e.g., addictions, severe depression) and when crisis management or day hospitalisation are unable to contain the patient.

Follow up studies show that remission is common – 74% after 6 years; 88% after 10 years – questioning the notion that this is a chronic, unremitting condition. There appears to be two clusters of symptoms, one (characterised by anger and feelings of abandonment) tends to be stable or persistent while the other (characterised by self-harm and suicide attempts) is unstable or less persistent. It should be clarified that in most cases remission actually means a reduction in the number of symptoms below the diagnostic threshold and not necessarily the complete resolution of the disorder.

Remission is also high when diagnosis is made during adolescence; the peak frequency of BPD symptoms appears to be at 14 years of age. However, in spite of the high remission rate, the presence of BPD in adolescence is far from harmless.

Apart from the already mentioned complications inherent to the disorder, diagnosis increases the risk of other negative outcomes. For example, 80% of teenagers with BPD will suffer from a personality disorder in adulthood, even though BPD will occur in only 16% of them.

Reference

Cailhol L, Gicquel L, Raynaud J-P. Borderline personality disorder. In Rey JM (ed), IACAPAP e-Textbook of Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Geneva: International Association for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Allied Professions 2015.

Last updated 10/1/2022

POLICIES for Treatment of Mental Disorders. The project coordinator is Dr Allan Mawdsley. The version can be amended by consent. If you wish to contribute to the project, please email admin@mhyfvic.org

[6] Standard Treatment

a) Outpatient psychotherapies, medication and procedures

b) Inpatient psychotherapies, medication and procedures

c) Ancillary support services

[6 a ] Outpatient psychotherapies, medication and procedures

MHYFVic advocates that Specialist mental health services should offer a range of therapeutic programs for disabling mental health problems in the community. All disorders in childhood require wholistic management involving caregivers.

Service provision, clinical research and training should be integrated in the Tier Three facilities, with the practice guidelines published by those services implemented at all levels of their service delivery facilities. The baseline standard of case assessment required is that outlined in PE4 (and PE2a(i) for infant mental health)

POL6a (vii) Personality Disorders

MHYFVic advocates that Specialist mental health services should offer comprehensive assessment and treatment programs for children with behavioural disorders. Such services would include ongoing collaboration with families and consultative support to other agencies involved in the management plan. It would also include components for management of challenging behaviours.

Last updated 29/1/2022

BEST PRACTICE for Treatment of Mental Disorders. The project coordinator is Dr Allan Mawdsley. The version can be amended by consent. If you wish to contribute to the project, please email admin@mhyfvic.org

[6] Standard Treatment

a) Outpatient psychotherapies, medication and procedures

b) Inpatient psychotherapies, medication and procedures

c) Ancillary support services

[6 a ] Outpatient psychotherapies, medication and procedures

Specialist mental health services should offer a range of therapeutic programs for disabling mental health problems in the community. Service provision, clinical research and training are closely linked in the Tier Three facilities but the practice guidelines published by those services should be implemented at all levels of their service delivery facilities.

These are grouped under nine headings: (i) organic brain disorders, (ii) substance abuse disorders, (iii) psychotic disorders, (iv) mood disorders, (v) anxiety disorders, including stress-related, somatoform and obsessive-compulsive disorders, (vi) physiological disorders, including eating, sleeping and sexual, (vii) personality disorders, (viii) intellectual disability and developmental disorders including autism spectrum disorders, (ix) behavioural and relationship disorders of childhood.

All disorders in childhood require wholistic management involving caregivers. See PE4 for a general outline of case identification and assessment and PE2a(i) for infant mental health. See PE6a(ix) for a general outline of case management for young people.

BP6a (vii) Personality Disorders

Personality is the enduring pattern of social, emotional and behavioural traits that uniquely characterise each person. Personality disorders are enduring patterns which are maladaptive by deviating from cultural norms and causing distress and social disability. For communicative purposes these trait patterns are customarily clustered into a small number of recognisable types [Paranoid, Schizoid, Schizotypal, Antisocial, Borderline, Histrionic, Narcissistic, Avoidant].

In acknowledgment of the huge changes taking place during a young person’s development, it has been customary to avoid stigmatising young people with diagnoses of personality disorder until beyond age 18. Nevertheless, many of the traits are firmly established before the age of 18. Early recognition of maladaptive traits and early treatment may be of major importance to the eventual outcome, irrespective of the formal use of the diagnostic category.

Two particular examples of patterns commonly seen in young people are Antisocial Personality Disorder and Borderline Personality Disorder.

ANTISOCIAL PERSONALITY DISORDER

‘Externalising’ childhood behavioural disorders are classified in a gradation from ’Disruptive Behaviour Disorder’ to ‘Oppositional-Defiant Disorder’ and ‘Conduct Disorder’ before merging into the adult diagnostic category of ‘Antisocial Personality Disorder’.

Although one half of conduct-problem children do not grow up to have antisocial personalities, the antisocial boys develop into adult men who are depressed, anxious, socially isolated, and have low-paid jobs. Thus, all conduct-disorder children warrant clinical attention.

Best practice in a specialist mental health service will include wholistic management involving child and caregivers together with collaborative support to relevant community partners such as schools. The assessment and case management will incorporate the principles outlined in PE4 and the range of therapeutic modalities necessary for such case management, such as family therapy, parent guidance (including behaviour modification) and child psychotherapies.

If the child’s disruptive behaviours manifest in delayed development in one or more areas the psychologist is likely to assess cognitive function and developmental markers. This can be very important in identifying children who have learning disabilities which may be affecting their academic performance and their capacity to learn. Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), a developmental disorder of the neurological impulse-control system, are at risk of developing disruptive behaviour disorders.

BORDERLINE PERSONALITY DISORDER

The main characteristics of BPD are instability and impulsivity, as described in PE6a(vii). The pattern of behaviour must be enduring, inflexible, pervasive across a broad range of personal and social situations and must cause significant impairment or distress.

Best practice in a specialist mental health service will include wholistic management involving child and caregivers together with collaborative support to relevant community partners such as schools.

The assessment and case management will incorporate the principles outlined in PE4 and include:

The range of therapeutic modalities necessary for such case management includes family therapy, parent guidance (including behaviour modification) and child psychotherapies (including Cognitive Behavioural Therapies).

Last updated 29/1/2022

We welcome discussion about any of the topics in our Roadmap epecially any wish to develop the information or policies.

Please send your comments by email to admin@mhyfvic.org

Speak about issues that concern you such as gaps in services, things that shouldn’t have happened, or things that ought to happen but haven’t; to make a better quality of service…….

Help achieve better access to services & better co-ordination between services together we can…….

Mental Health for the Young & their Families in Victoria is a collaborative partnership between mental health & other health professionals, service users & the general public.

MHYFVic

PO Box 206,

Parkville, Vic 3052

Please fill in the details below and agree to the conditions to apply for MHYFVic membership.