WINSTON RICKARDS ORATION

The 2020 Winston Rickards Memorial Oration which was deferred from its originally planned date because of the Covid-19 pandemic, was re-scheduled for April in 2021 but, sadly, had to be postponed yet again. We acknowledge that the Royal Children’s Hospital restrictions on visitors could not be relaxed to allow the necessary audience.

Unfortunately, the hospital is still in the same situation, so we have decided to hold the postponed Oration in the Ian Potter auditorium of the University of Melbourne Brain Centre, in the Kenneth Meyer building, 30 Royal Parade, Parkville (entry next to the Dr Dax kitchen).

The Oration will be held on

Wednesday 16th March 2022 at 7.30pm.

Covid-vaccinated-only bookings are required:

https://www.trybooking.com/BWQBW

The event is to honour the lifetime of dedicated service to child mental health by our founding President, Winston Rickards. We would prefer it to be a free event but are faced with major venue costs that we can ill afford. We are therefore requesting a $15 donation by attendees during registration to help us recover costs. Donations are refundable if requested.

The event will be broadcast worldwide on Zoom. Anyone preferring to watch it on zoom will be given the link upon registration through TryBooking.

“The Elephant leaves the Room”

Professor Frank Oberklaid’s Oration will discuss the place of child and adolescent mental health in public health care.

Professor Oberklaid has spent most of his career in the University of Melbourne Department of Community Child Health, based at the Royal Children’s Hospital and in close collaboration with the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute. Increasingly, his work has come to focus on the importance of child mental health for our nation’s progress. His oration will highlight the significance of research in the field.

MHYFVic ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING

The MHYFVic Annual General Meeting was not able to be held as planned at Bleak House Hotel, but was held as an on-line Zoom meeting.

Sadly, Harry Gelber’s after-dinner talk, “Hearing the Voice of Children: reflections from a child engagement project conducted at the Royal Children’s Hospital” had to be deferred. We are planning to hold this at our 2022 Annual General Meeting.

This will be held on Wednesday 24th August. Details of venue and Notices will be given in a future newsletter.

Reducing childhood mental disorders

Decades of epidemiological research has shown that the prevalence of childhood mental disorders (predominantly anxiety and mood disorders) remains stubbornly high despite major improvements in services and in general health and wellbeing. This is because the incidence of new cases is similar to the combined rates of response to interventions and natural remission. The clear public health conclusion is that prevention of new cases is strategically more important than treatment in reducing prevalence.

The very first section of MHYFVic website discussion of prevention of mental disorders highlights the national significance of social aspects of the problem in the following words:

“Children from more advantaged backgrounds not only have lower vulnerability rates but as a whole they make better progress. In fact, the gap between the haves and have-nots widens as time goes by. Studies of developmental progress of children of high, medium and lower initial achievement levels find that children from more privileged socioeconomic backgrounds make better progress at all levels than comparable children from deprived backgrounds. Within the socio-economically advantaged group the higher-functioning children make much better than average progress, the average children make good progress and even the developmentally challenged children make progress towards the average range. By contrast, disadvantaged children with early signs of potential struggle to maintain that promise; the developmentally challenged fall way behind.

It is not just money, but how families are able to use their money to best effect. Advantaged families generally have better-educated adults with better employment and higher aspirations. They value education, read more, converse more, and have high expectations of what their children should do. They generally spend more time on their children’s activities and if there are vulnerabilities are more likely to recognize these and arrange support.

The socially disadvantaged, on the other hand, are struggling to make ends meet. They may well be working several menial jobs at odd hours that leave them little time to spare for their children. Although they hope for their children to have a better life, it is difficult for them to do much to make it better, especially if they have not had a good education themselves. They are often unable to meet the special needs of vulnerable children.

This socioeconomic disadvantage translates into a biological slipway. The poor have shorter life spans, higher rates of heart disease, obesity, type two diabetes, smoking and substance use. Recent evidence also indicates impaired brain function.”

Having highlighted a major problem area, the section then posits the public health dilemma of what to do.

“Poverty is by far the most important factor negatively correlated with mental health. Improvement in safety, housing, food and welfare is the single most important universal intervention in the relief of mental disorders. As poverty is the strongest adverse factor underpinning prevalence of mental health disorders in children and families, it would seem logical to expect alleviation of poverty to reduce prevalence. The limited available research information on income support payments to impoverished families does not show evidence of improvements in adverse child experiences of domestic abuse, child maltreatment, parental mental illness, parenting practices or marital separation. There is no available long-term follow-up research. Similarly, there is no mental health improvement stemming from welfare reform initiatives like employment training, financial counselling and minimum wage legislation, notwithstanding ample evidence of the negative effects of unemployment and poverty.”

In addition to the alleviation of poverty, the MHYFVic discussion goes on to advocate strengthening of family functioning, improving social supports and promoting education towards every individual reaching his/her potential. The final section discusses alleviating what it refers to as “toxic events”.

A recent MHYFVic newsletter reported that the Centre of Research Excellence in Childhood Adversity and Mental Health, based at the Murdoch Institute within the Royal Children’s Hospital, is undertaking a five-year research program to evaluate an integrated Child and Family Hub model of care. The focus is on alleviating toxic events. Their recent newsletter makes the following comments:

“Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are stressful and potentially traumatic experiences during childhood that can have negative impacts and lasting effects on health and well-being. Researchers consistently find that early childhood preventive interventions targeting ACEs can reduce the substantial burden of common mental disorders and suicidality in the population.”

“Compared to their same aged peers, children who experience adversities or adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) are 6 to 10 times more likely to develop mental health problems later in life. ACEs are defined as stressful and potentially traumatic experiences in childhood. They include physical, emotional and sexual abuse or neglect, bullying, parent mental health problems, harsh parenting, parent substance abuse and housing problems. What happens now has sustained, long-term impacts; not only on children’s wellbeing and long term outcomes but on the future social and economic wellbeing of our communities. Targeting interventions to reduce these risk factors during the early childhood years could help to reduce depression, anxiety and suicidality and improve the mental health and wellbeing of Australian children and the adults they will become. However, despite substantial evidence demonstrating the benefit of investing in the early years of life, interventions targeting the precursors of mental health disorders – i.e. children’s emotional and behavioural problems – do not always reach the families most in need. The vision of the Centre of Research Excellence in Childhood Adversity and Mental Health is to create a sustainable service approach. This approach, co-designed with end-users, aims to improve children’s mental health by early detection and by responding to family adversity in evidence-based ways.”

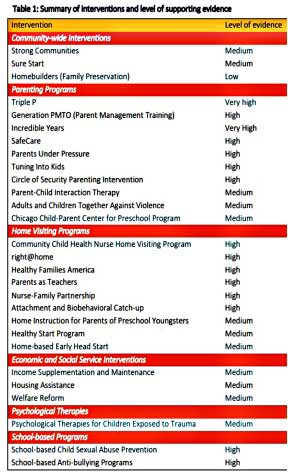

Their preliminary step was an evaluation of available evidence on intervention methods, which produced the following table:

Child and Family Hubs are being co-designed and tested in two Australian communities (Wyndham Vale in Victoria and Marrickville in New South Wales) to see what interventions are most effective for reducing the negative effects of adversity and adverse childhood experiences on children’s mental health. The work will be conducted through a series of different research projects and led by a multidisciplinary team of experts in psychology, mental health, parenting and paediatrics as well as front line service providers and people with lived experience.

MHYFVic has for some years been strongly advocating implementation of such projects. It is most rewarding to report that it is happening, albeit on a small scale. We keenly await the outcomes of the research and the implementation of effective programs on a universal scale.

Reference

Sahle B., Reavley N., Morgan A., Yap M., Reupert A., Loftus H., Jorm A. Communication Brief: Summary of interventions to prevent adverse childhood experiences and reduce their negative impact on children’s mental health: An evidence based review. Centre of Research Excellence in Childhood Adversity and Mental Health, Melbourne, Australia, 2020

wordSmyth: trauma

Jo Grimwade

Welcome to an understanding of words that are part of therapeutic practice. Somehow the way we use words creates the possibility of truth and the probability of being misled. Here, we look at trauma (etymological enquiry is aided by several large dictionaries that I access, as listed, below. Other references are provided, as relevant). This column is a replacement for the long running: History Corner. I am sure there are many stories to be told about past practices of family mental health. Its institutions, and its buildings, but until asked about other items of interest, the archaelogy of words will replace the archaeology of practices and places.

Trauma is the Ancient Greek word for “a wound. A hurt, or a defeat” and was first used with medical Latin in the 1690s. It comes from the proto-Indo-European as “trau-” from the root word “tere-“meaning “to rub or turn”, which includes derivatives of twisting and piercing. It was a term for physical injury from a specific event.

In the late nineteenth century, a new usage emerged for a psychic wound or an unpleasant experience, with the source of the wounds was still external but the wounds were manifested in behaviour and emotions, not necessarily observable or external in origin.

The etymology is confusing because there is a German word, Traum, which means “dream, vision” and is of Mid High German origin. Attempts to link the Greek and the German centre on the word for “to deceive”, which is Trügen. This gets even more complicated as (the Strachey translated) Freud wrote of the traumatic effects of the First World War, as well as endlessly on dreams! But it was a contemporary neurologist of Freud’s who made the connection with psychological effects of external events.

In the 1800s there was an athletic movement that symbolized the entering into the modern world of a German state founded on masculinity, healthy muscularity, patriotic service, and economic productivity (Schatzman, 1973). Schatzman, following Freud’s lead, examined the case of paranoia in eminent jurist, Daniel Schreber and the mistreatment he received as a child from his father, a prominent advocate of athletics as a healthy lifestyle and a diversion from adolescent interest in sexuality.

By contrast there was an enlarging group of working-class men who suffered from changes in industrial conditions and were no longer able to work (Lerner, 2004). This was attributed to a failed psychological state of men with weaker nerves. In the military, these were men who were deemed to be shirking their patriotic duties and seeking to acquire a pension.

However, in 1889, a Jewish neurologist and a Berliner, Hermann Oppenheim proposed the theory of traumatic neurosis describing pathogenic effects of accidents and shocks (Lerner, 2004). Oppenheim also wrote the standard textbook on neurology, Textbook of nervous diseases, in 1894, which included his theory of traumatic neurosis, or hysteria virilis (male hysteria), and which was reprinted in seven editions (including translation into English, Russian, Spanish, and Italian).

For Oppenheim, the blame fell on the external, traumatic event, rather than on character failings of the sufferer. In 1916, the issue came to a head in a medical conference, and it was concluded that feeble-minded soldiers, lacking in patriotism, were seeking a pension: rather than displaying the reactions of persons to the horrors of war. Oppenheim (Lerner, 2004) was cast out and questions were raised about Jewish patriotism that would be echoed in the Second World War.

That is, the version of German manhood was a political conception that was challenged by the experience of war trauma and had to be shut down and turned into something of ridicule.

The debate about what trauma is survives in another form today. In mental health services, trauma, which is an external event is not a psychological problem to be treated by mental health professionals. Children in out of home care who suffer trauma are often not treated in CAMHS because of their unsafe environment and the priority of the need to protect. These children suffer internally, from external events.

But this invokes words and myths for another time.

References

Collins Dictionaries. (1996) Collins English Dictionary (complete and unabridged). Glasgow: Harper/Collins.

Lerner, P. (2004) Hysterical men: war, psychiatry, and the politics of trauma in Germany, 1890-1930. New York: Routledge.

Macquarie Dictionary (Eighth Edition). Sydney: PanMacmillan.

OED. (2021). Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Schatzman, M.(1973). Soul Murder: persecution in the family. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

OUR UPDATED WEBSITE

After much thought our website has been significantly revised to give casual visitors immediate information about what we do and what we stand for, whilst at the same time allowing members to go straight to specific sections such as Projects or Newsletters or Events, without having to navigate past reams of information.

Now that the main revision has been implemented we are working on tasks of development of Projects to give us the evidence base for our advocacy. There are quite a few items under development at the present time which are not yet reflected in the website but over the next few months we expect to see a burgeoning of activity.

Visit us on mhyfvic.org

* President : Jo Grimwade

* Vice-President : Jenny Luntz

* Past President: Allan Mawdsley

* Secretary : Cecelia Winkelman

* Treasurer/Memberships: Kaye Geoghegan

* Projects Coordinator, Allan Mawdsley

* WebMaster, Ron Ingram

* Newsletter Editor, Allan Mawdsley

* Youth Consumer Representative, vacant

* Members without portfolio: Suzie Dean, Miriam Tisher, Celia Godfrey.

Mental Health for the Young & their Families in Victoria is a collaborative partnership between mental health & other health professionals, service users & the general public.

MHYFVic

PO Box 206,

Parkville, Vic 3052