Mental Health for the Young & their Families in Victoria is a collaborative partnership between mental health & other health professionals, service users & the general public.

Mailing Address

MHYFVic

PO Box 206,

Parkville, Vic 3052

PROJECT EVIDENCE for Prevention of Mental Disorders.

The project coordinator is Dr Allan Mawdsley. The version can be amended by consent. If you wish to contribute to the project, please email admin@mhyfvic.org

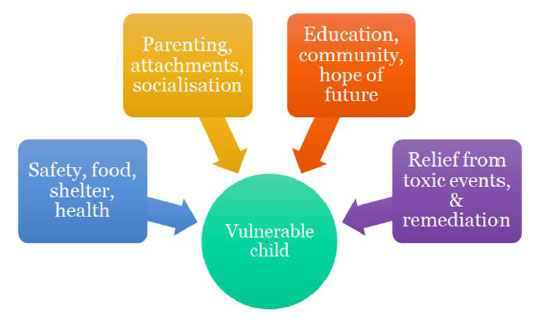

[1] Universal Programs. Universal programs are desirable because they have the potential to reduce the community prevalence of mental disorders whereas Selective and Targeted interventions only focus on small sub-populations. A discussion of this can be found in the 2018 Winston Rickards Memorial Oration which can be accessed on the MHYFVic website. The Oration puts forward the hierarchy a,b,c,d below, based on the World Health Organisation literature on Prevention of Mental Disorders.

These aspects of prevention form a kind of hierarchy of significance, somewhat similar to Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. (If you are in a war zone, unsafe, with no reliable food and water, no shelter and no support services, there is a high level of stress and not much else matters.) Once these basic needs are met there is time to look at family functioning and parenting. Enhancement of attachment and pro-social behaviours then become feasible, paving the way for processes to reach one’s potential and to respond to individual therapeutic interventions.

[1 a] Safety, housing, food, welfare

Children from more advantaged backgrounds not only have lower vulnerability rates but as a whole they make better progress. In fact, the gap between the haves and have-nots widens as time goes by. Studies of developmental progress of children of high, medium and lower initial achievement levels find that children from more privileged socioeconomic backgrounds make better progress at all levels than comparable children from deprived backgrounds. Within the socio-economically advantaged group the higher-functioning children make much better than average progress, the average children make good progress and even the developmentally challenged children make progress towards the average range. By contrast, disadvantaged children with early signs of potential struggle to maintain that promise; the developmentally challenged fall way behind. 1

It is not just money, but how families are able to use their money to best effect. Advantaged families generally have better-educated adults with better employment and higher aspirations. They value education, read more, converse more, and have high expectations of what their children should do. They generally spend more time on their children’s activities and if there are vulnerabilities are more likely to recognize these and arrange support.

The socially disadvantaged, on the other hand, are struggling to make ends meet. They may well be working several menial jobs at odd hours that leave them little time to spare for their children. Although they hope for their children to have a better life, it is difficult for them to do much to make it better, especially if they have not had a good education themselves. They are often unable to meet the special needs of vulnerable children.

This socioeconomic disadvantage translates into a biological slipway. The poor have shorter life spans, higher rates of heart disease, obesity, type two diabetes, smoking and substance use. Recent evidence also indicates impaired brain function. Neuroscientists used Magnetic Resonance Imaging to study the brains of healthy children from various socioeconomic strata. They report, “We confirm behaviourally that language is one of the cognitive domains most affected by Socio-economic Status. Furthermore, we observe widespread modifications in children’s brain structure.

A lower SES is associated with smaller volumes of gray matter in bilateral hippocampi, middle temporal gyri, left fusiform and right inferior occipito-temporal gyri, according to both volume- and surface-based morphometry. Moreover, we identify local gyrification effects in anterior frontal regions, supportive of a potential developmental lag in lower SES children.” This means reduced brain capacity in areas to do with expressive language, verbal reasoning and executive functioning such as planning and foreseeing the possible consequences of one’s actions. 2,3

Poverty is by far the most important factor negatively correlated with mental health. Improvement in safety, housing, food and welfare is the single most important universal intervention in the relief of mental disorders. As poverty is the strongest adverse factor underpinning prevalence of mental health disorders in children and families,4,5,6 it would seem logical to expect alleviation of poverty to reduce prevalence.7 The limited available research information on income support payments to impoverished families does not show evidence of improvements in adverse child experiences of domestic abuse, child maltreatment, parental mental illness, parenting practices or marital separation.

There is no available long-term follow-up research. Similarly, there is no mental health improvement stemming from welfare reform initiatives like employment training, financial counselling and minimum wage legislation, notwithstanding ample evidence of the negative effects of unemployment and poverty.

It is clear that by the time these reparative measures are introduced, the damage to family life and parenting has already been done and is not being reversed. Quality of life and adequacy of parenting need to be available throughout child development, not just provided retrospectively after failure.

Research on the effects of Universal Basic Income (UBI), however, does show an impact.

A comprehensive systematic review of the health impact of unconditional cash transfers found a 27% reduction in the likelihood of being sick, also improved food security and diversity, and school attendance of children. National and international studies of health, wellbeing and happiness show a positive correlation with wealth although diminishing returns for wealth beyond average standard of living.8

What is the minimum for a family to lead a healthy life? Data from the Social Policy Research Centre at the University of NSW in 2017 calculated that a single adult would need $600pw. A couple with no children would need $830pw. Add a child of 6 and that rises to $970. Add a second child and it is $1170. Of that, one third would go on rent and the remainder to cover all other costs. Current Social Security benefits fall short by at least $100 pw and minimum wage employment barely scrapes home with no time for nurturance of children.

The political debate about UBI hinges around the cost/benefit analysis. The estimated cost is very high, probably around $A350M per annum, which could only be achieved through high taxation and major taxation and welfare reforms. Sceptics argue that such a levelling of income disparity would be a disincentive to business investment and that people would work less, impairing economic growth.

A trial program in Manitoba did find slight reductions in hours worked during the experiment. However, the only two groups who worked significantly less were new mothers, and teenagers working to support their families. New mothers spent this time with their infant children, and working teenagers put significant additional time into their schooling. If this reduction is unimportant and the financial redistribution is recouped by taxation, the proponents argue that economic growth would be stimulated by the healthier population and greater participation in education towards higher skilled employment.9

Whilst the costs will be rapidly apparent, the benefits in terms of better health, wellbeing and achievements may not be fully demonstrable for a generation.10

The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare has been set up by the Council of Australian Governments as an independent body to monitor the performance of various health and welfare initiatives.

By agreeing on indicators, setting goals, measuring outcomes and reporting the results to inform further remediation, huge improvements have been made in public health, but comparable methodology has not been applied to welfare. Instead, ad hoc initiatives have been made in Social Security payments and perusal of child protection legislation. Until the AIHW systematically monitors welfare in a comparable way to its monitoring of health, it is unlikely that coordinated improvement will occur.

References

1. Centre for Community Child Health, Royal Children’s Hospital “The impact of poverty on early childhood development”. 2009. Policy Brief No.14.

2. Yu, Jing; Patel, Reeya A.; Gilman, Stephen E. “Childhood disadvantage, neurocognitive development and neuropsychiatric disorders: Evidence of mechanisms”. Current Opinion in Psychiatry: May 2021 – Volume 34 – Issue 3 – p 306-323 doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000701

3. Holz, Nathalie E.; Laucht, Manfred; Meyer-Lindenberg, Andreas “Recent advances in understanding the neurobiology of childhood socioeconomic disadvantage”. Current Opinion in Psychiatry: September 2015 – Volume 28 – Issue 5 – p 365-370 doi: 10.1097/YCO.0000000000000178.

4. Fryers, T; Melzer, D; Jenkins, R; “Social inequalities and the common mental disorders: a systematic review of the evidence.” Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2003;38 (5) 229-237

5. Dohrenwend,BP; Levav, I; Shrout, PE; Schwartz, S; Naveh, G; Link, BG; Skodol, AE; Stueve, A. “Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorders: the causation-selection issue.” Science 1992;255 (5047) 946-952.

6. Anton N. Isaacs, Joanne Enticott, Graham Meadows and Brett Inder. “Lower income levels in Australia are strongly associated with elevated psychological distress: Implications for healthcare and other policy areas” Front Psychiatry. 2018; 9: 536. Published online 2018 Oct 26. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00536

7. World Health Organization Mental Health Action Plan 2013-2020. Geneva: (2013)

8. Pega, Frank; Liu, Sze; Walter, Stefan; Pabayo, Roman; Saith, Ruhi; Lhachimi, Stefan “Unconditional cash transfers for reducing poverty and vulnerabilities: effect on use of health services and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries”. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11: (2017) CD011135. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011135.pub2. PMC 6486161. PMID 29139110.

9. Belik, Vivian “A Town Without Poverty? Canada’s only experiment in guaranteed income finally gets reckoning”. (5 September 2011). Dominionpaper.ca.

10. Bowman, D; Mallett, S; Cooney-O’Donoghue, D. “Basic income: trade-offs and bottom lines”. 2017. Brotherhood of St Laurence Policy Research Centre.

Last updated 12 September 2021.

POLICIES for Prevention of Mental Disorders

[1] Universal Programs

a) Safety, housing, food, welfare

b) Family functioning, parenting and Pro-social functioning (Human Capital)

c) Education to potential

d) Reduction of toxic factors

i Biological factors

ii Psychological and social factors

[1 a] Safety, housing, food, welfare

MHYFVic advocates that all families should receive housing and universal basic income support sufficient to ensure they are above the minimum requirements outlined by the Social Policy Research Centre of UNSW (or equivalent authority).

MHYFVic advocates that the Australian Institute of health and Welfare implements a process of identifying welfare indicators, setting goals, measuring outcomes and reporting results to inform remediation of welfare services.

Last updated 12 September 2021.

BEST PRACTICE MODELS for Prevention of Mental Disorders

[1] Universal Programs

a) Safety, housing, food, welfare

b) Family functioning, parenting and Pro-social functioning (Human Capital)

c) Education to potential

d) Reduction of toxic factors

i Biological factors

ii Psychological and social factors

[1 a] Safety, housing, food, welfare

Poverty is by far the most important factor negatively correlated with mental health. Improvement in safety, housing, food and welfare is the single most important universal intervention in the relief of mental disorders.

What is the minimum for a family to lead a healthy life?

Data from the Social Policy Research Centre at the University of NSW in 2017 calculated that a single adult would need $600pw. A couple with no children would need $830pw. Add a child of 6 and that rises to $970. Add a second child and it is $1170. Of that, one third would go on rent and the remainder to cover all other costs. Current Social Security benefits fall short by at least $100 pw and minimum wage employment barely scrapes home with no time for nurturance of children.

Best Practice requires housing and income support for all families to live at better than the abovementioned standard. The level of support needs to be regularly updated. The support needs to be combined with other measures proposed in BP1b, BP1c and BP1d.

Last updated 12 September 2021.

We welcome discussion about any of the topics in our Roadmap epecially any wish to develop the information or policies.

Please send your comments by email to admin@mhyfvic.org

Speak about issues that concern you such as gaps in services, things that shouldn’t have happened, or things that ought to happen but haven’t; to make a better quality of service…….

Help achieve better access to services & better co-ordination between services together we can…….

Mental Health for the Young & their Families in Victoria is a collaborative partnership between mental health & other health professionals, service users & the general public.

MHYFVic

PO Box 206,

Parkville, Vic 3052

Please fill in the details below and agree to the conditions to apply for MHYFVic membership.